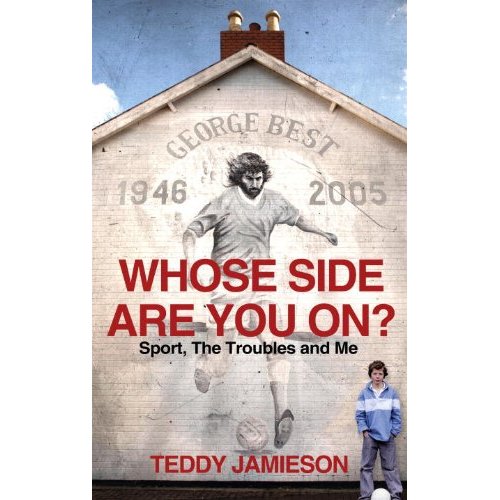

My second blog guest in as many months is the Herald’s excellent magazine writer Teddy Jamieson, whose first book (see right) casts a perceptive eye over the sporting landscape in the place where he grew up – Northern Ireland. Read on if you want to know which is the best supported football club in all of Ireland, how anybody could bring themselves to hate Mary Peters, and whether Irish stick-fighting is poised for a comeback.

Northern Ireland seems like the ultimate test bed for the question of whether sport unites more than it divides. How does it work out?

Northern Ireland seems like the ultimate test bed for the question of whether sport unites more than it divides. How does it work out?

The answer of course is both. The divisions are probably easier to see. In any society that is fractured and divided (and goodness knows, Northern Ireland is, was and maybe always will be divided) those divisions will be mirrored in all aspects of the society.

And so what flags are flown, what anthems are sung, who goes to see the games – all of these things are, in Northern Ireland, a statement of identity. They will mark out people and places and events as nationalist or unionist. If you go to a Gaelic football game and hear the Irish national anthem it doesn’t take a genius to know that the sport is based in the nationalist community. Similarly, if you go to Windsor Park and hear the British national anthem played before Northern Ireland international games then it’s clear there is a strong unionist identity being reflected here – although the Northern Ireland fans have been working hard in recent years to remove the sectarian tag that hung around them in the wake of the Neil Lennon death threat in 2002.

Lennon’s not the only sportsman or woman who was threatened because of his background. The likes of George Best, Mary Peters and Willie John McBride – all from Protestant backgrounds – received threats from nationalist paramilitaries, while Lennon, Pat Jennings and many, many Gaelic footballers and hurlers received threats from loyalist paramilitaries (or people purporting to speak for them). Indeed, tragically, many people associated with Gaelic sports were killed during the Troubles – some directly because of their links to the Gaelic Athletic Association.

Then again that’s not the whole picture. It never bothered me growing up that Dennis Taylor or Barry McGuigan came from a Catholic background. I was just thrilled that both were world champions and both were – like me – from Northern Ireland. I could enjoy the thrill of fellow feeling and not worry much about their religion.

Best may have been a boy from Protestant east Belfast, the son of an Orangeman, but his talent and his attractiveness meant he was loved by people from both communities. Oh and he played for Man United which is the best supported club in Ireland, both north and south, by both Catholics and Protestants.

That said, when I started working on the book I was a bit suspicious of the glibness of the idea that McGuigan fighting under a white flag helped bring people together, or that Mary Peters winning a gold medal was a uniting moment. But the more I thought about it and spoke to some of those involved the more I felt there was something in it.

For a couple of reasons. Yes, when Mary Peters won a gold medal in Munich in 1972 she received a threat the next day. But there were still thousands upon thousands of people in the streets of Belfast to celebrate her return a few days later. The same was true when McGuigan became world champion. Did it change anything? No. But did it change the moment? Yes. And that is something.

Which sportsman did you want to be in the playground?

Honestly? Umm, Gunter Netzer [excellent choice – Ed.]. I was very taken with the West German side of the early 1970s (partly because I was born in Germany; my dad was in the British army stationed there) and Netzer, the playboy Number 10, was my favourite player of the time. I liked George Best too, but he played for Man United and that was problematic for me (I was a Spurs fan myself – if I’d been a few years older I could probably have been happy pretending to be Danny Blanchflower).

In my teens I wanted to be Glenn Hoddle (though without the God-bothering), but if you want to know my ultimate Northern Irish sporting hero it would have to be Gerry Armstrong because of the goal he scored against Spain in the 1982 World Cup finals.

Has domestic football suffered from the Old Firm’s presence?

Growing up I didn’t know anyone in Northern Ireland who supported the Old Firm. Everyone I knew in the small town I grew up in supported English teams because that’s what we saw on the telly. It may have been different on the council estates of Belfast of course, but even now if you listen to phone-in shows on the radio you’ll find that most callers with Northern Irish accents will be United, Liverpool or Chelsea fans.

Of course anyone who has been on a ferry from Stranraer to Larne or Belfast on a Saturday night will know that quite a few fans travel to Ibrox and Celtic Park from the province. And I have noticed more and more Celtic and Rangers football tops being worn in the north since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

In the end, though, I’m not sure I’m the best person to ask about the Old Firm. In Scotland I’m a Stirling Albion fan.

Why did Ireland’s rugby team seem to be immune from the Troubles?

It wasn’t, is the quick answer. In the early 1970s Scotland and Wales wouldn’t travel to Dublin to play because of the Troubles (England did, it should be noted). And as I mentioned before Willie John McBride, an Ulster Protestant, received threats when captaining Ireland.

There’s also the case of Nigel Carr, an Ulster and Ireland player whose career was more or less ended when the car he was travelling in was involved in a roadside bomb in 1987.

But it’s true that rugby was a different case from football. Partly that’s because, after partition, the game remained under an all-island administration rather than being split in two. Ulster continued to play against the other Irish provinces so those connections were never severed. Ulster players would also travel to Dublin to represent Ireland.

There’s also a class element here too. In the north rugby was a game played by Protestant grammar school boys (Catholic schools played Gaelic sports). Down south it was fee-paying schools who played the game. It’s a middle-class game, in short.

Are there any signs of an Irish stick-fighting renaissance?

No, I think those who wanted to use sticks to fight with have tended to prefer baseball bats in recent years. American cultural imperialism gets everywhere, doesn’t it?

Tell me something I didn’t know about George Best.

Apart from the fact that he was an expert in Dutch 18th-century ceramics? Nah, it’s very difficult to find out anything new about Georgie given that his story has been told and retold so many times (though you might like to have a look for the Belfast poet Miriam Gamble‘s poem Tinkerness).

In the book all I have tried to do is locate George in a specifically Northern Irish context and ask why he was able to transcend the divide and be loved by both Protestant and Catholic. A lot of it is to do with the kind of player he was and the team he played for. It should also be remembered that he was a star before the Troubles really kicked off so his glamour was fully formed.

But like Alex Higgins he represents a working-class, peacock-feathered vision of Northern Irishness that’s hugely attractive (on the field or on the snooker table at least). It’s also a world away from the stereotypical vision of Northern Irish Protestantism – a kind of dour, never-on-a-Sunday, no-alcohol-for-me Presbyterianism. And that’s very attractive, especially for lapsed dour Presbyterians like me.

Whose Side Are You On? Sport, the Troubles and Me by Teddy Jamieson is published by Yellow Jersey, priced £14.99 (or less on Amazon). You can also follow Teddy’s blog here.

One thought on “Fighting colours: Talking Northern Ireland sport with Teddy Jamieson”